Today on the London tube I was reading the introduction to ‘The Monstrosity of Christ: paradox or dialectic?’, a debate between Slavoj Žižek and John Millbank, edited by Creston Davis, the latter the author of the introduction. My post here is not about the main subject matter of the book (two views of theology / christianity) but the final sentence of the introduction stayed with me for the day:

The monstrosity of Christ is the love either in paradox or in dialectics – and I believe, may be the pathway beyond the current popular-absolutist rule of finance, spectacle, and surveillance.

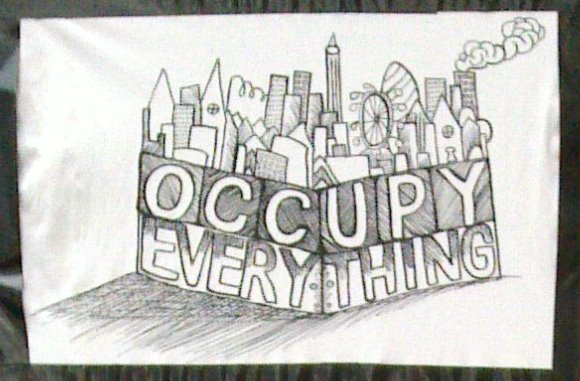

Although we can argue about the faith part of this (or even reject it out of hand), the two sides this statement resonate nowhere better right now than at tent city in the forecourt of St Paul’s cathedral, in the heart of the City of London.

By a stroke of luck my companion and I happened upon a talk entitled ‘The Corporate Governance of the Square Mile’ led by George Monbiot, John Christensen, and a Father Taylor, and so we spent the next 90 minutes inside the ‘Tent City University’ straining to hear a discourse that went right to the core of what is rotten in the city of London. The particular topic – the Corporation of the City of London (itself an archaic structure cunningly serving the needs of London square mile financial overlords and protected more by opaqueness than power) – is just a detail in the overall story of the economic disaster in which we find ourselves today. Stuart Fraser, Chairman of the Corporation of London had also come (into the lion’s den, so to speak) to right what he felt were/would be misspoken half-truths about the Corporation. Well done for that. A debate needs both sides present.

The talks were worthwhile (Rev. Taylor who has worked within the corporation of London, and spoke eloquently on it), and I will probably revisit the tent city for more. Everyone was civil, despite the yawning gulf between Monbiot et al (recent article on the Corporation of the City of London), and Fraser (who replies here to some accusations).

What struck me today was the composition of the audience, as well as the speakers. There is always a segment consisting of people boiling in furious rage (and I can’t necessarily judge them for it – for my own subjective reaction to the slow-burn fiasco of the state of the planet is one of dejected detachment – and that is hardly more defensible) who fail to make it past the expression of such emotions, and enter meaningfully into a discussion. Which means that rather than doing research, learning facts, and constructing analyses and arguments, they make noise. They are the voice of all of us, if we simply want to express rage. Yes, there were a few of those. But mostly, the crowd was educated, over 40, and articulate. Dressed just like me. Everyone seems to know that the whole game is rotten. We just can’t see how to act.

The sad thing I felt is that on the steps of St Paul’s this afternoon there was an awful lot of human intelligence, going unheard. What great debates could these 200 or so people entertain? We’ll never know, because there is no place for intelligent, normal people to effectively discuss the problems of the day, much less produce decisions on what to do about it. The best we can do is hope that our friendly neighbourhood iconoclasts such as Monbiot say the right things for us. But it really isn’t good enough. Such people can only articulate their view, and what they see as the priorities. We really need to do better.

My suggestion on how is to consider the main topic: money. We need to make individual efforts on a) understanding the monetary system (earlier in the day I bought a book called ’23 Things they don’t tell you about Capitalism’ by Ha-Joon Chang – as good a place to start as any) and b) start thinking about how to overturn it. No, I don’t mean in some incoherent revolutionary way, I mean by subtle means available to us, including digital currencies and local currency systems. I will elaborate on these in later posts.

For now – on a Sunday – it seems appropriate (irreligious though I am) to meditate on the deep malaise at the heart of today’s civilisation, and the tiny hope I have when I see hundreds of people just like me spending their evening at St Paul’s, not inside in the anaesthetised comfort of worship-as-usual, but outside in the blasting wind among the tents of the younger generation, looking for a different kind of salvation. I have a feeling that only we can create it.

To the tent-dwellers: I salute you. Maintain the rage.

Acknowledgement: Adriána Daniláková for the great photos 🙂

” Everyone seems to know that the whole game is rotten. We just can’t see how to act.

Well… that’s an improvement, anyway. I recall a time when taking the position that the social order really wasn’t working except for a very limited few was quite a lonely place. Especially if you didn’t agree with the Trotskyites.

For what it’s worth, I think you’re right about money as the heart of the problem. I’ve thought so for a long time. It’s essentially an abstract concept, a placeholder — but our damned monkey brains insist on regarding it as something concrete: a reward, a goal, a way of ‘winning the game’.

If you come up with anything interesting on the topic, let me know.

I think my major issue with it is the idea that profit necessarily equals some kind of public good. Profit is used as a measure of success, and in a coldly capitalist system, all human activity (and indeed, nonhuman activity as well) is judged on profitability.

I’m thinking it might be nice if we could deflect that in the direction of freedom of action. “Good” would be defined as “actions which overall increase human freedom of choice”. And actions which overall decrease freedom of choice or action would be morally unacceptable.

Of course, that means carefully examining any proposed action or choice. Very carefully. And more: it means putting aside some sacred cows, and examining the question of human rights such as the right to reproduce, for example…

… so I don’t think we’re going to get there.

Ultimately, money is too easy. It’s too effective. It makes abstract ideas of profit and ownership into something you can see and touch (in the form of cash). It’s the greatest ‘scorekeeper’ ever invented, and we’re locked into the game.

LikeLike

There are many things wrong with money when it gets out of control. I think the primary one is that it abstracts away the limits to resources. When humans bartered, you could only make trades with real goods or services that you actually had. Thus the total amount of ‘wealth’ available was limited to the productive capacity you had access to. If ‘you’ were not just an individual, but a guild, company, or national government, that could be quite a lot.

With money, this link to reality is lost. An estimate from about a decade ago was that there is 10x the amount of money in circulation as there are real resources to back it. Meaning: if everyone tried to convert their cash to land/goods/services, only $1 in $10 would get you anything (but of course who got there first would win).

What is happening at any point in time now is that financial instruments and other tricks of corporate mercantilism (e.g. the patent royalty system) have turned money into this elastic multiplier device from which fortunes are being siphoned off by those in control, and turned into land, yachts, mansions, cars, and private wealth funds, while the rest of us poor fools continue to work for a normal wage.

One thing that would change this is local currencies – local to a nation state (like we used to have in Europe) but more importantly local to geographic regions – what I would call ‘ground money’. This already exists on the fringes as LETS and other alternative money systems, but it could be systemically deployed. It would need to work such that some money people earned could be spent far away, or exchanged with distant currencies. But the basic principle could be used to link money with real productive capacity & resource, and also force tax paid by people in local currency to be spent by the tax collector (the govt) in that region.

Obviously derivatives and other instruments of the mentally sick would not exist.

LikeLike

We thank you for your comments, and greatly appreciate the ending. We have shard this in our twitter and fbook feeds.

Tent City University

Occupy LSX

LikeLike